The Possibilities of Kindness: Interview with SJ Sindu

Photo Credit: Sarah Bodri

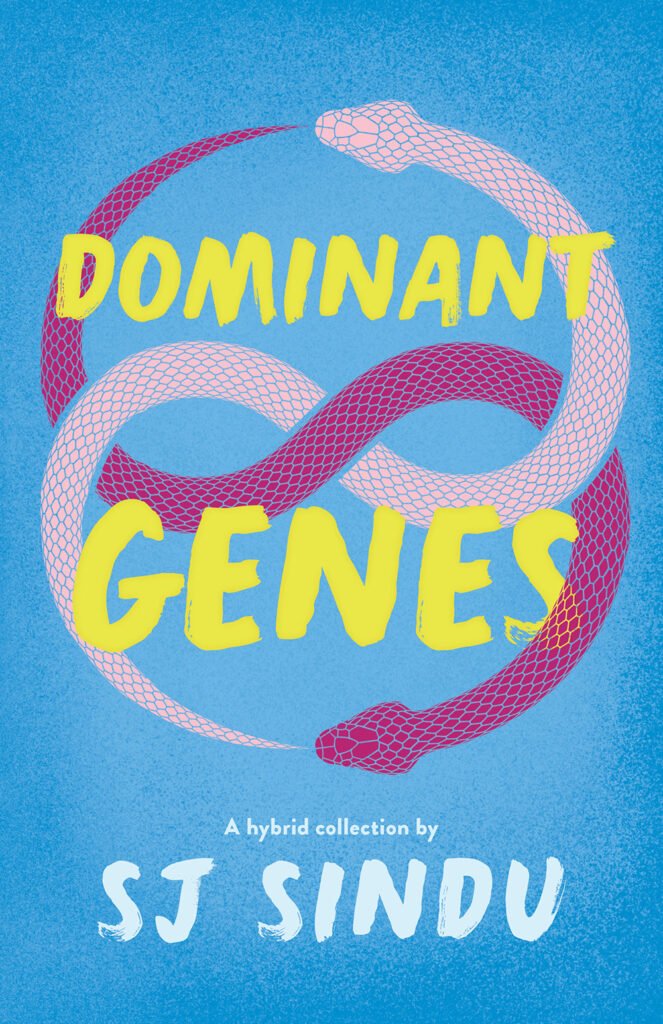

SJ Sindu is a Tamil diaspora author of two literary novels, two hybrid chapbooks, and two forthcoming graphic novels. Sindu’s first novel, Marriage of a Thousand Lies, won the Publishing Triangle Edmund White Award and the second novel, Blue-Skinned Gods, is currently a finalist for the Lambda Literary Award. Sindu’s newest work, a hybrid chapbook titled Dominant Genes, was published by Black Lawrence Press in February 2022. Sindu holds a PhD in English and Creative Writing from Florida State University and teaches at the University of Toronto Scarborough.

In this interview, Digital Content Editor Manahil Bandukwala talks to Sindu about Dominant Genes, which won the 2020 Black River Chapbook Competition. Dominant Genes is a hybrid collection of poetry and prose that explores family, faith, and connection.

To learn more, visit sjsindu.com or Twitter @sjsindu and Instagram @sjsindu.

Manahil: Dominant Genes is a hybrid poetry-prose chapbook. You’ve authored two novels as well as a previous chapbook of fiction and non-fiction. Is Dominant Genes your first collection to include poetry? Why did you decide to shift towards this inclusion?

Sindu: Yes, Dominant Genes is the first collection that has any poetry at all. Although I wrote poetry (very bad poetry) in high school, I didn’t take classes in poetry during my university or graduate degrees. I stopped writing it altogether. But then the pandemic hit, and I found myself unable to write for many months. I asked my partner, the poet Geoff Bouvier, to conduct a poetry masterclass for me in the first summer of the pandemic. This class he came up with—I was his only student—got me writing again, and most of the poems in this chapbook were written at that time. I realized at the end of that summer that I had a chapbook, but I also wanted to include some prose pieces because I liked the themes they brought to the poems, the complexities of scene.

Manahil: That sounds so wonderful! Have you noticed your poetic practice change and develop in the (almost) two years since then? Where do you hope for it to go?

Sindu: My poetic practice has tapered off, but I find myself bringing a poetic sensibility and a poet’s eye to my fiction work. I’ve developed a theory of plotting based on how turns work in a poem, and have used it in a wide variety of work. I hope I come back to poems again, but right now I’m happy to approach my fiction as a sometimes-poet.

Manahil: The opening piece in the chapbook, “Birth Story,” is a prose poem, and its position in the sequence makes it a kind of birth story to the narrative of the chapbook itself. How do you find the place where a narrative begins?

Sindu: I wrote “Birth Story” specifically to be the beginning of this chapbook. I wanted something that introduced all the elements at least very briefly, and so this very short piece introduces the mother-daughter relationship, the expectations put on women, the way women silence each other, the question of what we inherit from our mothers, and the motif of string and stitching and tying that I use throughout. That sounds like a very analytical answer, but it’s only analytic in hindsight. In the moment when I’m writing and piecing a collection together, I’m going by feel and instinct.

Manahil: The poem “Gods in the Surf” moves into the prose essay “Draupadi Walks Alone at Night,” signaling towards the movement of gods between genres. What considerations did you have in mind when deciding how to order the chapbook, especially when moving from one genre to another?

Sindu: The chapbook was actually in a very different order when I got the publication offer from Black Lawrence. I re-ordered it twice right before publication. I like to think about all the thematic elements, which pieces will introduce certain elements or develop them or complicate them, and what kind of experience I want the reader to have while reading. Thematically and emotionally.

Manahil: In “Sun God,” you write: “I’m full of bad questions.” The works in your chapbook are constantly asking questions that are “bad,” such as questions concerning suitors or wedding customs, but these “bad” questions resonate so much! I felt a familiarity reading them, and felt very seen. How do we unlearn what we have been taught as “bad”?

Sindu: I think it’s a long, long process of unlearning. At least it was for me. I’m just glad that I started so early. Around ten years old, I remember starting to question everything. I was obsessed with the anime Sailor Moon, and it was that show that started my questioning process. I was following the political conversations as new seasons were coming up to be dubbed into English, and the American studios kept deeming Sailor Moon too gay and so they kept changing it in substantial ways. That got the ball rolling for me.

Manahil: I love how you depict the relationship with God like that of siblings throughout the pieces in the chapbook. For example, in “My Parents Crossed an Ocean and Lost Me,” you write: “When I visit, we fight—God and I—for my parents’ affection. We’re siblings born too far apart in age to be friends.” Why were you interested in exploring relationships with god(s) in this chapbook, as well as in your other works?

Sindu: I get obsessed with exploring certain subjects in my work over a good chunk of years. My most recent obsession—which lasted from 2013 onward and has now mostly dissipated—was religion. I investigated it deeply in my novel Blue-Skinned Gods, but that was a distanced exploration because it was fiction, and fiction that was far away from my own life. So I wanted to explore my personal connection with religion and gods in Dominant Genes. I also wrote a graphic novel titled Shakti, which rewrites goddess mythology, forthcoming in 2023. At this point, I feel like I’ve plundered the topic enough… for now.

Manahil: I’ve definitely felt the same feeling of having “plundered the topic” in my own writing. How do you continue to write or find things to write about?

Sindu: Always be curious. Get obsessed with new things. I’m always on a hunt for new ideas, and I think the most successful writers are the ones who are able to not only generate a lot of new ideas but also find the ability to commit to one for long periods of time, enough to finish projects. How do you find new ideas? Experience the world is my answer. I try to travel in the summers. I socialize whenever I can. I try to embrace new experiences, to try things just for the sake of trying things.

Manahil: The titular poem, “Dominant Genes,” closes the chapbook, and at the beginning has the line “I came out faithless.” You then go on to complicate conceptions of faith, and how white patriarchy has made the term “faith” seem equivalent to something negative. But your poem pushes us to think about where these associations come from. Faith is a complicated relationship, much more so than simply “coming out faithless.” How does faith intertwine with genealogy and ancestry? How is it intrinsic to who we are?

Sindu: Faith is a powerful point of connection between people, and is often expected to hold families together. So when different family members have different relationships with faith, it can affect everything about day-to-day life and also about moments of celebration. What you celebrate, and how you celebrate, and why you celebrate—all of this is often so bound up with faith, as is daily and weekly routine of family life. I wanted to explore the complications of what that looks like for me, in my own family and life. And because my extended family is still close, questions of geneology and ancestry were fundamental to this exploration. The faith of the matriarchs in my family holds everyone in orbit. I don’t think faith is intrinsic to who we are—or rather, I don’t think it has to be. I think humans have always leaned toward faith, but I think we can have faith in things other than the supernatural. We can have faith in each other, in the possibilities of kindness, in science, in adventure.