"Reasonable Amount of Tenderness": Review of stephanie roberts' rushes from the river disappointment

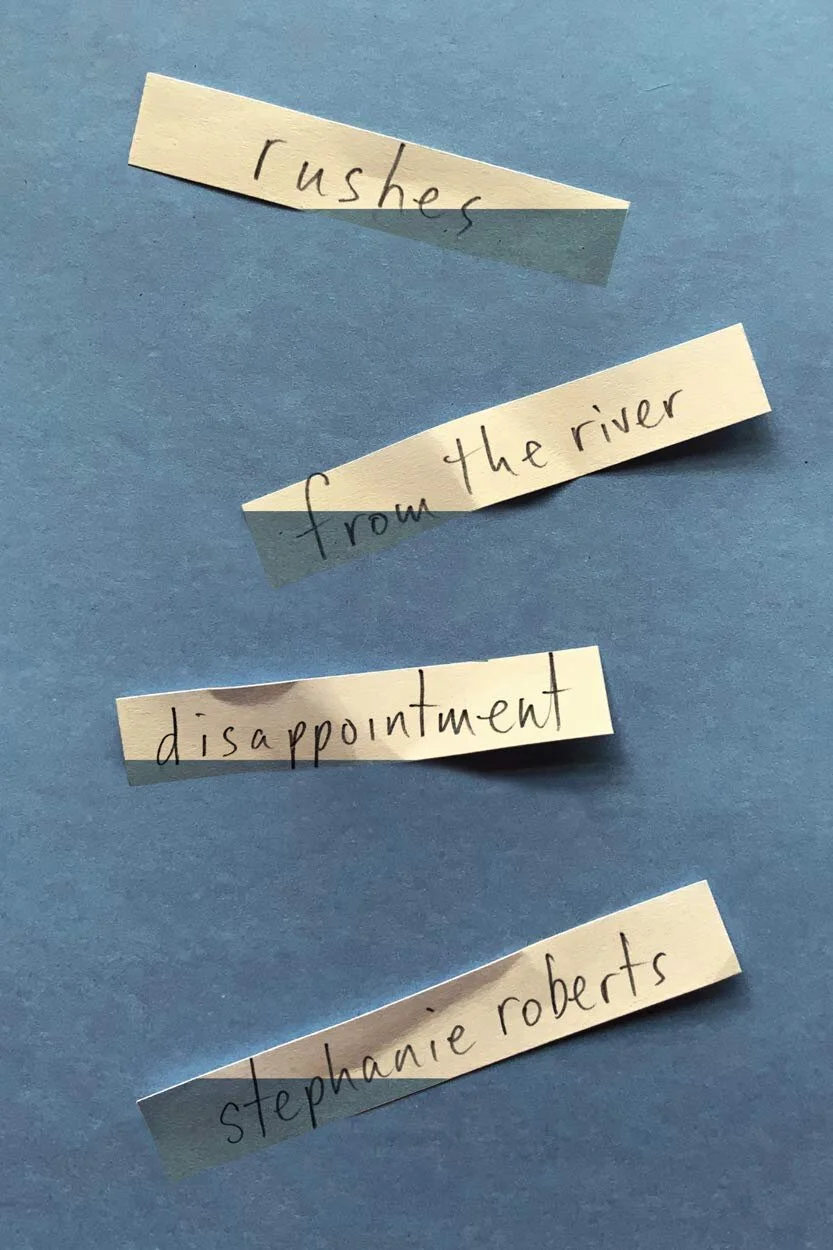

stephanie roberts, rushes from the river disappointment

McGill-Queens University Press, 2020. $17.95 CAD

Order a copy from McGill-Queens University Press

In her stunning new collection, rushes from the river disappointment, stephanie roberts takes us deep into a terrain of disappointment but also love, peopled both with believers and those who have seen too much to believe, where one’s “heart // muscle withers when you hope love is happening / and it isn’t” (22). There is world-weariness here, but one expressed with so much freshness that the reader roots for the cynic and the romantic alike.

The penultimate poem in the collection bears the same title as the book. Rushes are, of course, plants that grow on riverbanks and other low places, but I thought another meaning may also be apt, particularly since the poem refers briefly to a movie. In filmmaking, “rushes” are the raw footage from a day's shooting. The poems in the collection are not at all raw, although they are certainly tender—as in compassionate, but also in the sense of vulnerable and susceptible to bruising. They are highly polished and frequently use compressed syntax so that, both in the titular poem and throughout, there can be a sense of telegraphed sensations or coded impressions concerning the wonders and the failings of intimate relationships. It doesn’t seem wrong to consider these as the “rushes” from a speaker’s life. Alternatively, “rushes” could be a verb – with the collection musing on what exactly rushes from this river.

The poems are intricately crafted, in a wide range of styles: expansively-ranging lyric verse; narrow, sometimes right-justified, columns; poems enumerated as lists; and others laid out sparsely for maximum white space. The poet employs couplets to great effect in several poems, and she occasionally creates the feel of a ghazal, with leaps between seemingly disparate images and topics that are linked by emotional resonance. Her succinct observations can be almost like aphorisms or even koans: “a gobble of turkeys watch the train / where i – like god – eat a turkey sandwich” (54); “in the contorted bookkeeping of the broken, the distance you / hold yourself away from them is your only value” (98); “there are people capable of eating popcorn at the movie of your agony; do not marry him or him (note to my younger self)” (100).

As roberts noted in a Q&A session at a recent reading at Ottawa’s VerseFest, her identity is part of her art “whether I like it or not.” A citizen of Canada, Panama, and the U.S., roberts is a non-francophone and long-time Quebec resident. A political perspective is most clearly evident in “This Is about Being Black” and in “Catching Sight of The Pinta, The Niña and The Santa Maria” where the speaker sees the immanent colonizing force as “the apocalypse to come bearing a mizzenmast” (23). roberts noted in an interview with Annick MacAskill in Room Magazine that in her Latin household, “music AND dancing were a big deal” and music certainly features throughout rushes from the river disappointment, with references to Bob Dylan and Bon Iver, to Miles Davis and other jazz greats, to soul and Caribbean bachata (though the result of some supposedly relationship-saving bachata dance lessons is a “shuffle like a gross marionette” (95). Musicality is equally present in the poems, with lots of internal rhyme, assonance, consonance and rhythm: “crawl to the mound again moon & moth / again crawl to your salt mouth & song again / our moment held breath & horses” (76).

The collection includes beautifully evocative descriptions of nature. Human love and intimacy exist alongside the skies and storms, rivers and oceans, forests and animals (and are often intertwined with the natural elements). An insomniac walks “through trembling wombs of cedar / to the revelation of the lake’s pelvic girdle” (9). Life lessons are learned from plants: “The first loss wakes the heart to its task / sometimes forever” (39). In one of my favourite poems, “Germinate,” a relationship’s failures are viewed in concert with a root tendril splitting a seed-husk:

how little brash men consider June women opening

and the necessity of parting, as gently as possible, the hull.true, the nature of the rose is thorned (though a few haven’t any

while some emerge as barbed wire) stillevery thorn is red-born and bendable, they say, careful, in

husked tones, not, stay away. (90)

The language roberts uses is consistently gorgeous. The book is studded with highly original jewels about the moon and the sky: “waxing scimitar of moon” and “night’s quake of thin navy gauze” (4), “cadet-grey dusk / hues into prussian blue mystery” (9), “growing violet felt” (19), “moon pulls / bright fingers through / your exhausted navy clouds” (37), “navy velvet belly // of southern night” (56), “the blue shine // of your open night” (48), “wound and knotted round the purpling night sky” (90), “moon’s white-gold, loose-tooth grin” (94). Two moon poems in particular are rife with figurative language: “i never tire of the moon” calls the celestial object “god’s fallen lash, and lucifer’s lopsided smile” (19) while, in “Love Like a Waning Moon,” a series of metaphors and similes for impassioned love concludes with a final comparison: “sharp as the click / and swallow / of the word inexplicable / in the ocean’s moans of / why moon why?” (58).

The book features other motifs and preoccupations, including math and science. In navigating a relationship “it would help if we defined our variables,” so the couple can “pivot on our common denominator” (59). A speaker begs their beloved to “pay attention to my tender mathematics” (48) and “Twenty-Four Hours in the Life of a Frog” refers to theories by physicist Jim Al-Khalili. The book’s single long sequence uses physics formulae to map or track physical and emotional attractions and repulsions that equate, somehow, to love.

There is also a myth-like encounter between a polar bear and an owl, while other poems describe an owl that “will pass silent as a nightmare / from tree to memory” (9) and one with its “head on backward / eyes demented for scurry / tearing the blueberry night / apart” (58). Throughout the collection, roberts employs sensuality, humour and play, and brings in cultural references that range from Game of Thrones to a dedication to Lawson Fusao Inanda, the past Oregon Poet Laureate, to a social media quote mis-attributed to Shakespeare’s Ophelia, to Via Rail travel.

roberts’s poetry is well-published internationally and has been nominated for a Pushcart Prize, but she is perhaps less well-known in Canada. rushes from the river disappointment, which was nominated for the Quebec Writers' Federation’s A.M. Klein Prize, will hopefully change that since the book, and the poet herself, are deeply deserving of this recognition and many more.

Frances Boyle (she/her) is the author of two poetry collections, most recently This White Nest (Quattro Books 2019) as well as Seeking Shade, short stories (The Porcupine’s Quill 2020) and Tower, a Rapunzel-infused novella (Fish Gotta Swim Editions 2018). Her poetry has been selected for Best Canadian Poetry, and nominated for Best of the Net, and her writing has been published throughout North America, in Europe and in India. She lives in Ottawa. For more, visit www.francesboyle.com, and follow @francesboyle19 on Twitter and Instagram.