Review of Charlie Petch's Why I Was Late

Charlie Petch, Why I Was Late.

Brick Books, 2021. $20 CAD.

Order a copy from Brick Books.

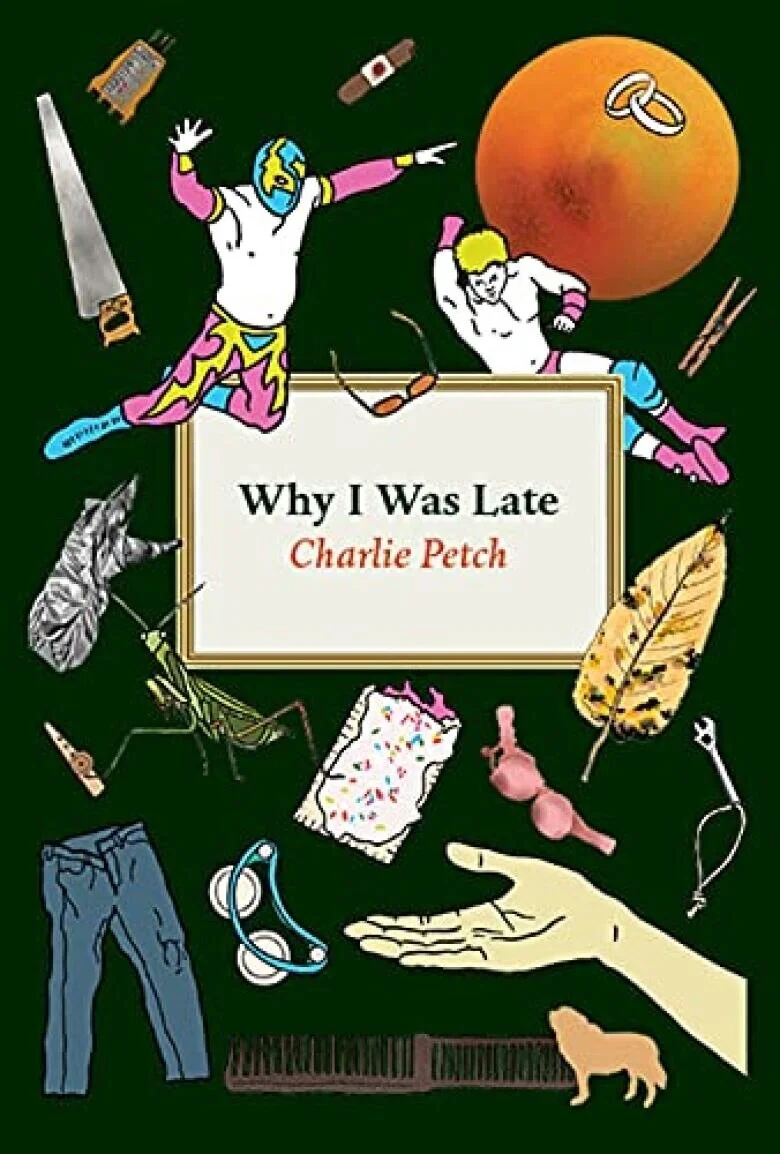

Charlie Petch’s debut book, Why I Was Late, interrogates masculinity through the nuanced perspective of a transmasculine, disabled, musical, theatre, Star Wars-loving person. Without reading the book, the illustrations on the cover may seem random or disjointed; however, upon reading, the cover acts as a map of easter eggs for us to find as we read. It is a beautiful moment to share with the author when you stumble upon a poem about a praying mantis or a musical saw and remember the illustration from the cover.

Petch is intentional with how the reader consumes each of the poems: there are stage notes included at the beginning of several of their poems. The first poem “Dear C3PO,” for example, is preceded with the directions: “To be accompanied by a ukulele & musical saw build on loop pedal, done to the tune of ‘You’re Just Too Good To Be True’ by Bob Crewe & Bob Gaudio” (11). In this way, each poem, though written for the page, is meant to be a performance. The consumption of each poem is not a passive process but rather one that immerses you in the moment Petch chooses to share with you.

Petch speaks about masculinity through a myriad of different contexts. They share their intrapersonal and interpersonal reflections on the masculinity of themself and of the men they have encountered throughout their life. Petch writes with an air of romance about their first boyfriend in the poem “My First Boyfriend,” using descriptions like, “Your mouth full of shy” and “callused with summer” (13). However, this is not to say that Petch writes with rose-tinted glasses. Rather, Petch also includes gut-punching lines about masculinity. In this same poem, the last stanza reads, “I remember the boy you might have been / step carefully past sumac bush / did you know it was poison then / that enemies smell sweetest / that betrayal is a part of growing up / that my first boyfriend / started off heroic?” (15). Not only do these last lines summarize a painful and honest reflection on the archetype of what is many people’s first boyfriends, the discomfort we as readers are faced with with these reflections are a testament to Petch’s vulnerability in speaking about masculinity for all that it is: the good and the bad.

Though there is no shortage of stories that Petch or others could tell of men who have committed harm, the tales of masculinity in this book are multilayered and nuanced. In “My First Lisping Hero,” Petch speaks about Mike Tyson’s masculinity in regards to his boxing, his lisp, his deadbeat father, and his daughter’s death. In this poem, we are given a full and multitudinal image of Mike Tyson and his masculinity. A powerful line in this poem is as follows: “maybe what you needed / was a male embrace / not to be cut short by a bell” (65). Petch humanizes and gives depth to the tale of this professional boxer. We learn that masculinity is not all about violence, but is also about the fight to be and want for better for one’s self. The poem ends with the lines, “some humans are capable of so much / when we give them a chance / to get up off the mat” (66).

We learn of the many intersections of masculinity with other identities through the collection. In “Schoolyard Theatre,” Petch speaks about their performance of masculinity in the lines, “these moments of male / started the slow feeling / that my skin was drag” (19). This metaphor of ‘drag’ is used by Petch throughout the book, and later in a poem titled “I’m So Good at Drag,” to describe the way they previously performed gender. We see the influence of their trans identity in several poems, which is distilled well in the poem “How Did You Get So Strong? Potential Answers,” where lines like “My breasts don’t belong to me, / so in a way, / some of it didn’t happen” and “I want to be seen as a man. / Isn’t this how to be a man?” (92) appear. This life experience clearly shapes the trajectory of their relationship with masculinity and their poetry reflects this greatly. This relationship is illustrated best in the title poem with the lines “someone took my body / and when they were done / they handed it back to me / neatly folded / and said / ‘keep this in a safe place’ / and now I can’t find it” (52). This relationship with the body is one that is explored greatly but, ultimately, is a lifelong journey that Petch graciously shares parts of with the reader.

Ultimately, Petch’s debut book is like none other. It is one that interrogates the main narrative of masculinity through all of its facets and gives a rich image to many tales of this life experience. Through Petch’s intersectional approach, we gain a deeper understanding of why exactly Petch “was late.”

Namitha Rathinappillai (she/her) is a Tamil-Canadian spoken word poet, artist, and writer who has entered the poetry community in 2017. She has been involved with Urban Legends Poetry Collective (ULPC) ever since her engagement with the Ottawa arts community, and made ULPC history as the first female and youngest director. She is a two-time Canadian Festival of Spoken Word (CFSW) team member with Urban Legends Poetry Collective, and she published her first chapbook, Dirty Laundry with battleaxe press in November 2018. She has been involved as a performer and a workshop facilitator within the Ottawa community at spaces such as Tell em Girl, Youth Ottawa, the Artistic Mentorship Program, Carleton Art Collective, The Fembassy, Youth Services Bureau, and more.