Carn(iv)al Delight: Review of Anna van Valkenburg's Queen and Carcass

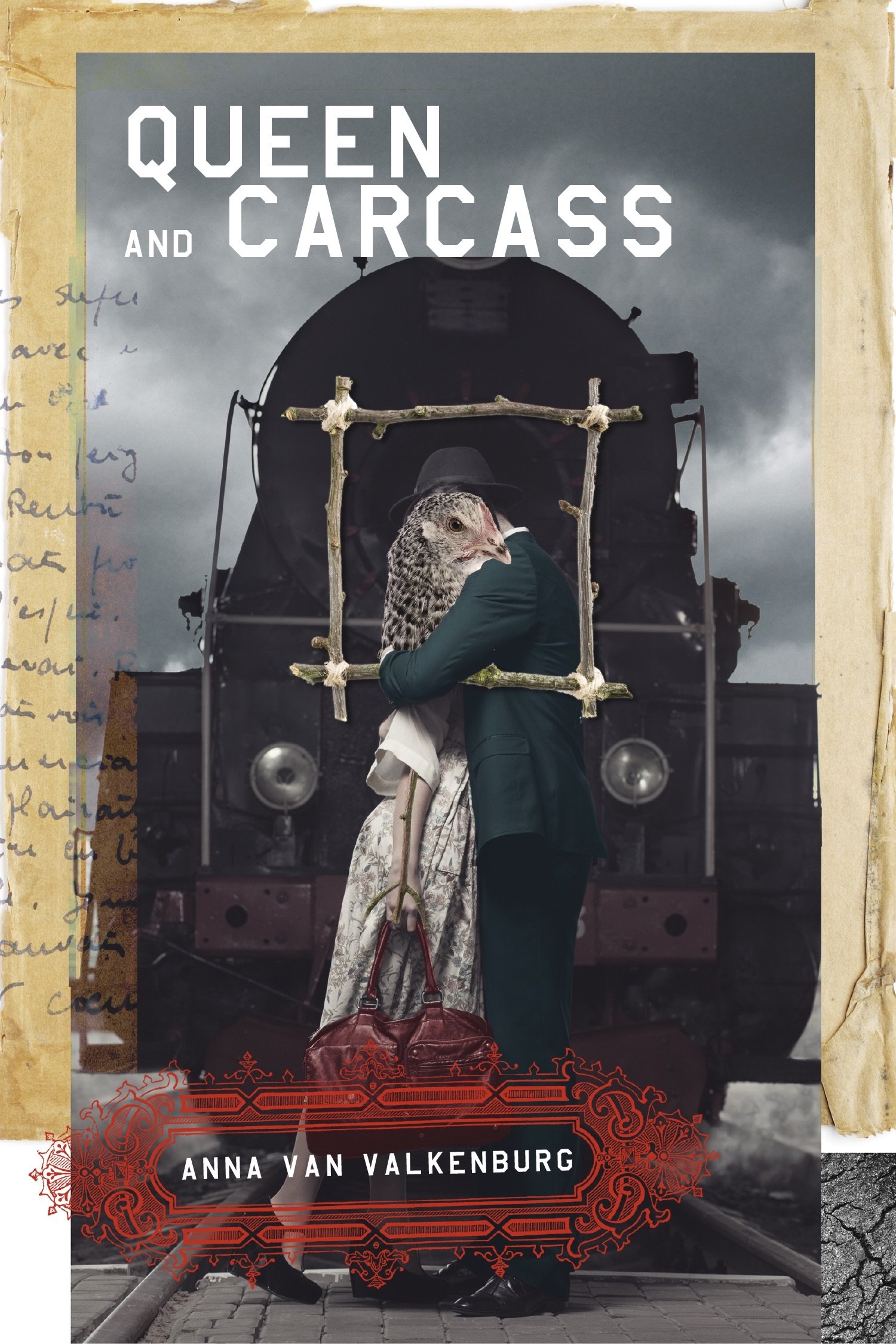

Anna van Valkenburg. Queen and Carcass.

Anvil Press, 2020. $18.

Order a copy from Anvil Press.

Content Warning: This review mentions the death of children.

The poems in Anna van Valkenburg’s debut poetry collection Queen and Carcass are self-contained: each one a seed-grain splitting open, or maybe an egg, revealing bent and twisted new bodies, wet with life-giving substance. There was an HBO show, Carnivale, which aired in the early 2000s and depicted the lives of various members of a travelling carnival in the Dust Bowl during the Great Depression in the 1930s. Queen and Carcass brings to mind the quirks, characters, and magico-bleak atmosphere of that HBO showcase of surreal gifts.

In “A Portrait of Serving Girls as Nightingales,” van Valkenburg writes of serving girls quibbling over tasks, a rooster spitting devotions into the sky before decapitation, ominous cows, and then turns to a dream the speaker is having, happening now. She writes: “inside these girls, there are / one thousand others / carrying the peeps / and squawks of every / bird that dared / snatch a currant (26-27).”

The farmlands and slant threats of violent fairy tales abound, as in “Little Red in Love”: “I’m the bone in the soup, / the dog’s dark feet / after rain; what remains / when the second letter of the alphabet / bites the first while waiting its turn, / and the mother throws a scowl (33).”

These are poems in which humans seem to be in the middle of a continuous spectrum between roads and skies, where a number of birds and farm animals trot out their lives and deaths. I get the sense that these are intimate poems, entities to be read one-on-one, or passed between lovers: “One day the distance / between / myself and you / will disappear (41).”

The collection was published in the fall of 2020, which means that most likely these poems would have all been written prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. There does seem to be a moody prescience of impending catastrophe that hasn’t yet tipped over into something nameable. In a nod to the famous William Carlos Williams poem, “This Is Just To Say,” van Valkenburg’s speaker asks us, “Do you feel the chill of time? It’s a frozen plum. / When it thaws it will be edible / again, you will have to deal with it then. / I think you are already thinking / about where you will hide tomorrow (43).”

In my reading, I see this “hide tomorrow” issue as two-fold: first, where will the listener nestle into the future in some intentional way? And second, if we could tuck tomorrow away, hide it in some cubby hole and forget about it, we might not have to deal with coming catastrophes, apocalypses, and all manner of unhappy endings. Van Valkenburg’s existential urgencies posit a choice: whether to hide ourselves in the future, or whether to hide the future from ourselves. Annihilate ourselves through change, or annihilate others through resistance to change. Van Valkenburg’s poems are short, but their endings tend against sweetness, each poem like a fruit with a bitter drupe stone at its centre.

There are odd inversions: a dead child and his murderer, now entered into the carceral system. The truth that sadness makes us happy. A man with tongues for arms comes to spread silence. Fish choke on smoke. There is startling imagery: the speaker sits “up straight like hard rain (73)”; “The sun drops into the hot- / sauce jar (56)”; “The drought has been peeling / our gardens since April (77).” There are prose poems both intimate and joyful (joyful despite xyz) that relish dark and dirty flexions in domestic locales.

One of my favourite poems, “Lessons in Philosophy,” imagines Plato bursting into a profane rage at the sight of the speaker’s daughter drawing thirty-seven yellow suns into a notebook: “Some are concentric, some layered. / Some have rays. Some have edges / like cracked bones. Some are skewered meat (80).” And at the end of the poem: “My daughter yells ‘Another!’”

In reading Queen and Carcass, I feel as I imagine the daughter in “Lessons in Philosophy” feels: ready for more of van Valkenburg’s poetry, for more of these small, surreal, and glowing systems of pleasure, death, and especially, of warmth. This collection of folk surrealist poetry is a lesson in precision, visual thought, and unique, energetic, and acrobatic syntax. The poems are a true delight: dark and sticky like taffy.

Margo LaPierre is a Canadian freelance editor and author of Washing Off the Raccoon Eyes (Guernica Editions, 2017). She is newsletter editor of Arc Poetry Magazine and member of poetry collective VII. She is the winner of the 2021 Room Poetry Award and the 2020 subTerrain Lush Triumphant Award for Fiction, and was shortlisted for the 2021 Fiddlehead Creative Nonfiction Contest. She is completing her MFA in Creative Writing at UBC. Find her on Twitter @margolapierre.